Unpacking with CivicStory: Green Infrastructure

Unpacking with CivicStory: Green Infrastructure

What is Green Infrastructure?

Green infrastructure is a blanket term encompassing different stormwater management systems that mimic the natural water cycle by using natural materials to improve water quality while preventing pollutants from entering our waterbodies.

“In New Jersey, we pay most attention to three things…flood mitigation, water quality improvement, and groundwater recharge,” said George Guo, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rutgers University. “These are explicit quantifiable benefits. We actually can size these to say, ‘There used to be this much flooding, and if I do this, how much flooding will be reduced?’”

The Problem

Stormwater is one of the largest obstacles to clean water in the United States. Also known as runoff, stormwater tends to run along hard surfaces such as roofs and driveways, making their way onto the street. Along its journey, this water usually collects pollutants like fertilizer, oil, dirt, and bacteria, pulling them into storm drains. The drains then carry the impure water through a network of underground pipes and release it into our streams, rivers, lakes and oceans.

Source: Pexels

Stormwater is most frequently found in urban and suburban neighborhoods where most of the land surface is covered by infrastructure like buildings and roads which produce more runoff than natural landscapes such as forests or grasslands.

Solution #1: Rain Gardens

A rain garden encompasses native plants such as grass, sedges, wildflowers, shrubs, and trees planted in an area set slightly below the surrounding ground along a natural slope. It is designed to slow water flow by absorbing and temporarily holding stormwater from roofs, driveways, and patios, and can soak up about 30% more water than traditional lawns. The root systems of native plants also support beneficial microbial communities that naturally break down the contaminants carried in the runoff.

This approach:

Improves water quality by naturally filtering out pollutants.

Supports local biodiversity like bees, butterflies, which aid pollutant breakdown.

Require limited maintenance as native plants are already well-adapted to their environment.

Beautifies urban communities by creating attractive green spaces that enhance neighborhood appeal and increase property values.

Increasing vegetation also helps to mitigate the heat island effect in urban cities by replacing heavily heat-absorbing surfaces like asphalt and concrete with shade trees, plants, and groundcovers, creating a natural cooling effect.

“Rain gardens are also the easiest…that’s what we try to advocate or convince residents to do first, " Guo said. “A lot of people are already gardening around the house.”

Solution #2: Rain barrels

Rain barrels are designed to collect roof water from the gutter’s downspout and conserve it for future use in watering lawns and gardens.

Nationwide, 30% of daily water use is outdoors, according to the U.S. EPA. Over half of this goes to gardens and lawns, totaling more than 9 billion gallons per day. By using rain barrels for these residential green spaces, we can better conserve water resources, thus reducing utility costs and lessening stormwater impact.

This approach:

Prevents stormwater from becoming runoff, keeping water bodies cleaner.

Saves our drinking water resources.

Provides a clean, chlorine-free source of water for green spaces, promoting healthier plant growth.

Is low maintenance and cost-efficient.

Source: Adobe Stock

In New Jersey, The Regional Partnership of Somerset County, the Borough of Manville, and the New Jersey Water Supply Authority offer rain barrel rebates of up to $200 for Somerville, Bridgewater, Raritan, and Manville Borough residents.

You can also find these at local home and garden supply stores like Home Depot.

Solution #3: Green Roofs

A green roof is a roofing system that involves adding a layer of vegetation to a traditional, flat commercial or residential roof. It typically includes a roof deck, waterproof membrane, root barrier, a growing medium such as soil, and plants including moss, grass or flowers.

In Pennsylvania, green roofs currently capture 50-60% of rainfall, returning water to the atmosphere, and preventing it from entering the stormwater system.

This approach:

Reduces peak runoff and slows down stormwater release by 3-4 hours.

Provides habitat for various species of wildlife.

Enhances urban aesthetics.

Cuts cooling costs by up to 70%.

Source: Adobe Stock

Green roofs also double as an effective strategy for reducing the heat island effect by providing shade, absorbing more heat from the atmosphere, and lowering surrounding surface temperatures. According to the EPA, green roofs can be up to 56°F cooler than conventional roofs and can reduce surrounding air temperatures by as much as 20°F.

According to Guo, the greatest challenge of this solution is its high cost. While state and federal programs typically cover construction, ongoing maintenance is the responsibility of local residents.

Green roofs provide some stormwater retention but are considered to have a relatively limited impact in managing large volumes of water and still produce overflow, a side effect common to all green infrastructure.

Make sure to check your local government’s website for any applicable tax credits for installing green roofs. Current programs include the Green Roof Tax Credit Program by the city of Philadelphia.

Solution #4: Permeable Surfaces

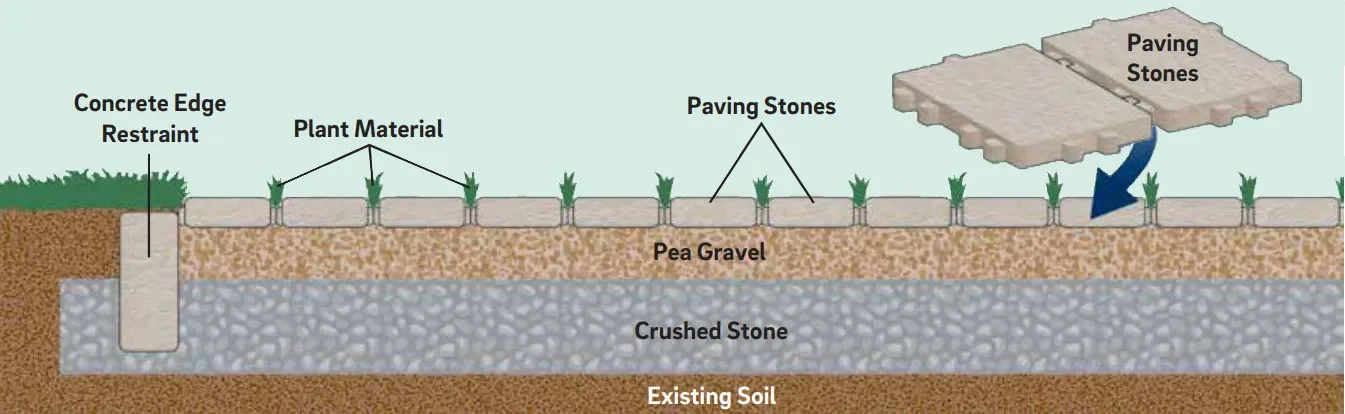

Permeable surfaces, including porous asphalt, interlocking pavers, and plastic grid pavers, allow runoff to seep into the soil through their larger void spaces while filtering out water pollutants.

A common example of this in practice is porous parking lots, driveways, and sidewalks. These surfaces can absorb up to 80% of stormwater runoff, drastically reducing flooding and erosion.

This approach:

Improves groundwater recharge, which is good for the ecosystem

Helps prevent pollution and flooding from urban runoff

Reduces reliance on traditional drainage systems, allowing for more green space

source: Philadelphia Water Department

A major challenge of these surfaces is maintenance, as it can clog over time and requires specialized cleaning like vacuuming, making it unsuitable for high-traffic streets.

To increase effectiveness, Guo recommends adding a large gravel layer beneath the surface, which essentially functions as an underground reservoir.

Studies show that porous asphalt can survive over 20 years with proper maintenance, making it a long-term practical solution for cities or residents willing to invest in upkeep.

Why Now?

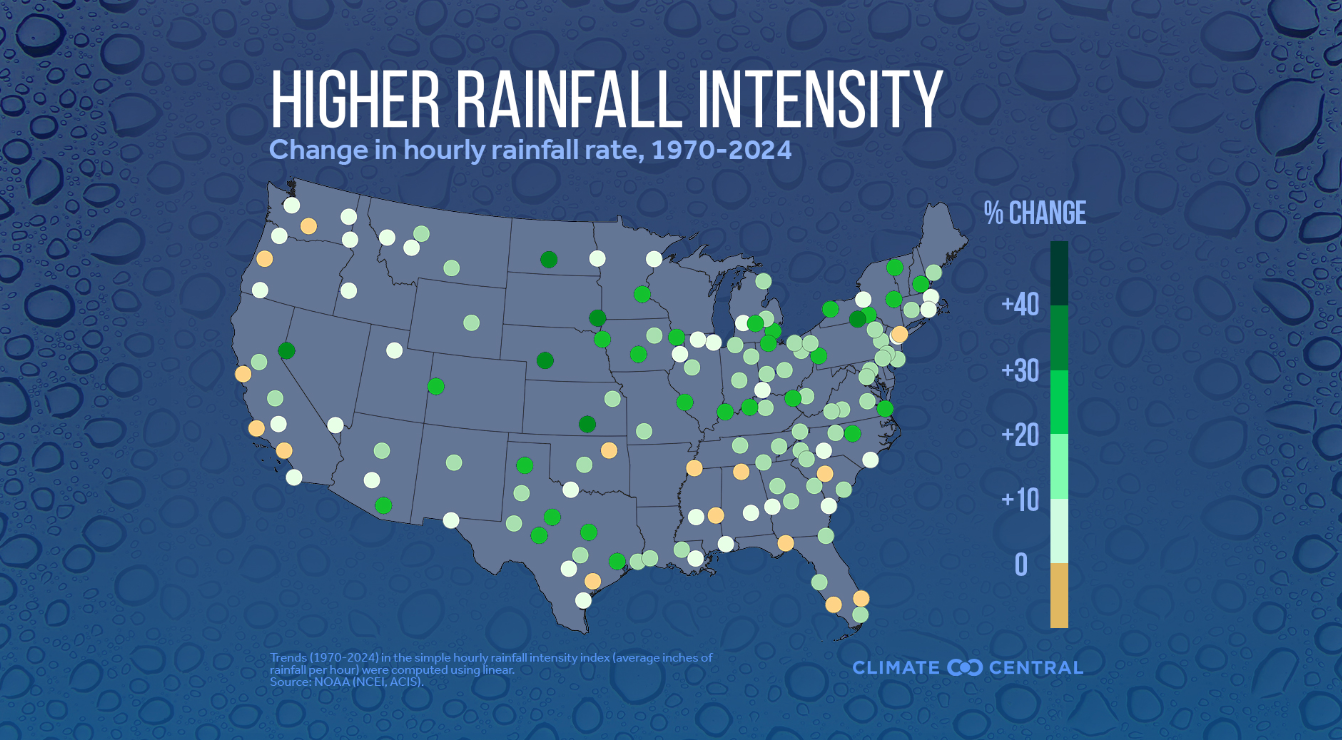

As climate change drives more extreme weather conditions such as heavier rainfall and longer dry periods, adaptation strategies become essential.

In the United States, 126 cities have seen an increase in hourly rainfall since 1970, with rates now 15% higher than they were then. However, Guo emphasized that rainfall intensity matters more than total volume, as these extreme weather events can overwhelm existing systems.

Source: Climate Central

Green infrastructure can help by providing additional storage during storms and supporting resilience during droughts, but it is not a one-size-fits all solution and must be integrated with other systems. In a major storm, Guo advocates using a combination of green infrastructure, gray infrastructure like pipes and drainage systems, and blue infrastructure such as water bodies.

“As a designer or planner you need to see what is the best combination not just to solve the problem but also think about the costs and land availability," Guo said. “I am for green infrastructure, I just don’t want to say it can do everything.”

He explained that excess water needs a safe passage when green systems are overwhelmed. While New Jersey’s proximity to the ocean provides a natural outlet, water still must be safely transported there, making pipes essential even in green-focused designs.

The Jersey Take

Stormwater management is required in New Jersey under N.J.A.C. 7:8, enacted in 2021 by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP). This regulation sets standards for managing runoff, protecting water quality, recharging groundwater, and minimizing erosion and flooding for new development or redevelopment. It encourages green infrastructure as part of best management practices and requires developers and municipalities to design, implement and maintain systems that meet these standards.

Local governments also encourage stormwater management through stormwater utilities, which appear on residents’ water or utility bills and charge property owners based on the amount of impervious surface they have, such as roofs, sidewalks, driveways, and parking lots.

Under New Jersey’s stormwater utility programs, property owners can receive fee reductions or credits if they install and maintain stormwater management practices, including green infrastructure like porous sidewalks. By converting these impervious areas to permeable surfaces and meeting approved standards, property owners can not only avoid fees but also contribute to a more liveable and healthy neighborhood ecosystem.