Behind the scenes of free and fair elections in New Jersey’s Warren County

William Duffy is the Board of Elections’ administrator, and Robert Stead is a commissioner, in Warren County, New Jersey

This is the busy season for Boards of Elections in New Jersey counties.

“Every day becomes more hectic, culminating in E-Day,” said Robert Stead, a commissioner on the Board of Elections in Warren County. He was referring to Election Day, which falls on November 8 this year.

Election operations and integrity have come under scrutiny nationwide in the wake of baseless claims of voter fraud during the 2020 presidential election. Warren County, in the northwestern part of New Jersey, provides a good illustration of election law in action.

New Jersey, like all states, has laws governing how elections are held and run. The state requires each county to have a Board of Elections with 4 to 6 commissioners, equally divided among the two parties whose General Assembly candidates received the most votes in the most recent general election – currently Republican and Democrat. The governor-appointed commissioners and their professional staff conduct legal oversight of elections in the county.

Stead, who is one of four commissioners in Warren County, is a Kearny native who retired after a career in the airline industry and, more recently, overseeing CPR instructors at Atlantic Health System. He has served continuously on the Board of Elections since 2006, motivated, he said, by the belief that smooth and lawful elections are “the foundation of our democracy.”

Preparing for elections

Warren County officials begin planning for any election at least two months in advance. Voting equipment is checked and prepared, poll workers are recruited and trained, and the ballot is created by the County Clerk, the chief election official in all 21 New Jersey counties.

The work of the Warren County commissioners is supported by a full-time administrator, a role filled by William Duffy since 2010. Duffy manages election logistics, personnel, and documents, and liaises with state and county officials.

Each of Warren County’s 89 polling sites is overseen by a chief poll worker, who reports to the administrator and the board of elections. To ensure adequate staffing, the county aims to overstaff to ensure coverage in case poll workers become sick or cannot report on Election Day. Poll workers are recruited via news media, political parties, and word of mouth.

“One of our best ways of recruiting is our own poll workers,” Duffy said. “They tell family and friends.”

A recent statewide increase in pollworker pay has helped with recruitment, he added. Poll workers now receive $300 a day for their service, paid for via county and state funds, and poll worker reimbursement pay is not subject to New Jersey state income tax.

Voting in person

The commissioners and their staff visit polling sites throughout the county on Election Day and during the early voting period to ensure the election is running smoothly, and troubleshoot any problems.

“We’re kind of like a quick-reaction force if there’s an issue,” Stead said.

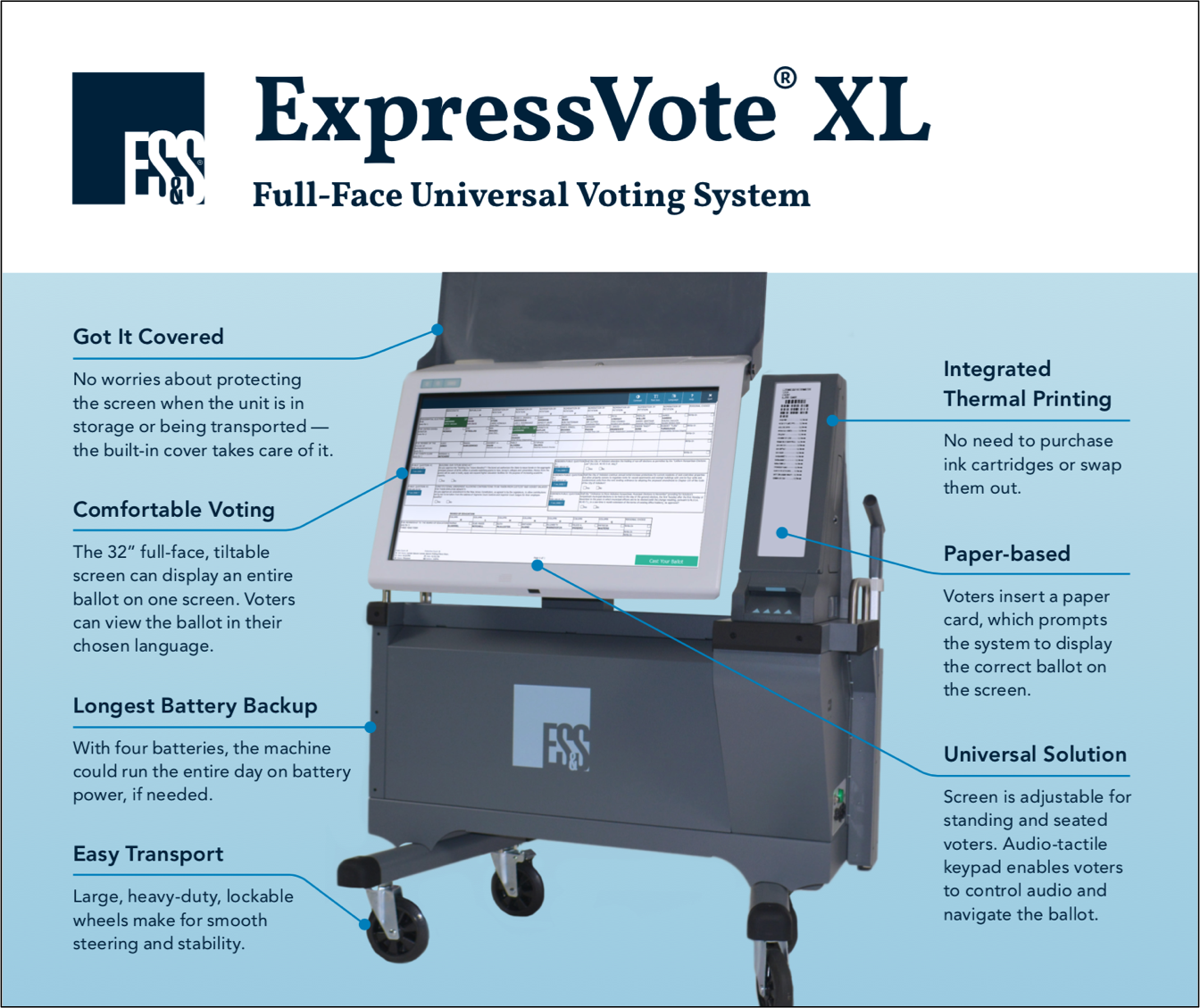

Warren County’s voting machines are manufactured by Election Systems & Software, and certified by the State of New Jersey. Photo credit: ES&S

When a voter arrives to vote at their designated polling place in Warren County, a poll worker checks their name and identifying information against the information the person provided when they registered to vote.

The poll worker encodes a blank paper ballot with a barcode specific to that voter. When the ballot is placed in the voting machine, it activates a voting screen showing all offices and issues for which the individual is eligible to vote. Choices made on the screen are recorded on the ballot. The machine then captures the paper ballot and records the votes on a computer drive.

When the polling station closes, the chief poll worker transports a tally tape showing the number of votes to the County Clerk, and the drive containing results from each machine to the county’s Board of Elections headquarters, which in Warren County is in Belvedere.

Early voting was implemented for the first time this year in New Jersey. For the upcoming general election, early voting will start on October 29 (the tenth calendar day before the election) and end on November 6 (the second calendar day before the election). Warren County has three early voting sites from which residents can choose.

“Wherever you live in the county, you can vote at one of those sites and those machines will be programmed with every ballot for every office in every municipality in the county. So if you live in Phillipsburg, you can come to a site in Blairstown,” Stead said. The encoded ballot will direct the voting machine to produce the slate that is specific to the voter.

Voting by mail or drop box

There was a one-time spike in the portion of general election ballots cast by mail or drop box in 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic necessitated a primarily vote-by-mail general election across the state, but those methods of voting have otherwise increased steadily in Warren County for years.

Ballots submitted by mail or drop box accounted for 6.5 percent of all Warren County ballots cast in 2013. By last year’s general election, they were close to 20 percent of the 37,273 ballots that the county’s voters cast.

Voters must carefully read and follow the instructions on vote-by-mail ballots to ensure their vote is counted. One of the biggest reasons ballots are rejected, according to Stead, is that people neglect to sign the certificate attached to the inner envelope containing the ballot, which they must place into the mailing envelope.

Stead has also seen unusual vote-by-mail mistakes: One voter placed not only his ballot in the envelope, but also checks to pay his electric bill and mortgage. Another voter included wedding pictures.

“There are some funny ones, and then there are some that are very traumatic,” Stead said, noting that since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Board has received more than one return containing a death certificate rather than a ballot, mailed by a relative of the deceased.

When Board of Elections officials receive vote-by-mail ballots that they deem defective in some way, a “cure” is often possible. In such cases, the officials immediately send a “cure letter” that offers the voter the opportunity to fix the problem and have their vote counted.

“If it's just a matter of a [missing] signature, there are a number of ways for you to respond: take a picture of your driver's license and text it to us, or mail it to us,” Stead said. “But sadly, it's a very low percentage of people who actually respond to that. I think it's because they feel the election is already over and your vote doesn't matter.”

Stead said that each vote does matter, noting that he has overseen elections that were decided by “one or two votes.”

In addition to carefully following instructions, voters should plan to place their ballot in the mail or an election drop box well in advance of Election Day. The drop boxes, which were introduced in New Jersey in 2020, are locked at 8 p.m. on Election Day. Mail-in ballots must be postmarked by Election Day, but the state allows until the Monday following the election for them to arrive through the mail.

“We've only rejected a very few ballots—like single digits—because they were delivered late,” Stead said. “And in every case they were mailed from distant places.”

Tabulating election results

The drives from all the voting machines are plugged in to a tabulating machine that generates the results. Under normal circumstances, Warren County Board of Elections officials do not physically count the paper ballots, which are locked inside the voting machines. However, the machines are temporarily impounded per state law, with the ballots inside them, in case of a legal challenge to the result, or a demand for a recount. If a hand count of ballots is required in such situations, the paper ballots are removed from the machines and counted.

Vote-by-mail results are added to the totals, and all provisional ballots deemed valid by the Board of Elections are scanned and added to the vote tabulations too.

When elections are close and candidates question the results, Duffy said he and the County Clerk “get all the information together: we get the tally tapes together, we get the mail-in ballots together, we get the provisional ballots together…We invite in the candidates and say, ‘Take a look. Tell us where we made a mistake.’”

In almost all such cases, candidates do not see evidence of any mistake, and they decline to demand a recount. The most recent election for which Duffy could recall conducting a recount was in 2013, when just 18 votes separated two candidates for county sheriff in a Republican primary contest.

“It took us from the middle of June until the middle of September to straighten it,” Duffy said. But when the recount was completed, “the 18 votes held up.”

Election integrity safeguards

Stead noted that since he was appointed as a commissioner 16 years ago, improvements in election technology have made elections increasingly secure.

“The concept of changing tallied votes to obtain a different result? Impossible,” he said.

Stead said voting machines cannot be digitally hacked, because the machines that voters use to cast their votes—which must be certified by the State—have no components that would allow them to connect to the internet.

“You might be the greatest hacker in the world, but there's no way you can hack our machines because there's nothing in there to hack,” Stead said.

The voting machines are also physically secured at the polling location until picked up the day following an election, and the paper ballots inside them are in a locked bin with a seal that would indicate tampering if broken.

“Physically or electronically, you cannot gain access to the [data in the] machine,” Stead said.

The digital drives containing the data from voting machines used in Warren County resemble standard flash drives, but they are proprietary to the voting machines.

“It's not like you could go to the store and buy a piece of computer equipment, like a flash drive or something, and download the votes,” Stead said. And even if someone could overcome the challenge of finding a substitute for the device that captures the data from the machine, the data is encrypted to a level equivalent to that used by the Department of Defense, he added.

“Most people are familiar with a two-step authentication concept, right? Ours has several more steps” known only to the commissioners and the administrator, said Stead.

What if a drive were to go missing? In that case, Stead said, the Board of Elections would go back to the voting machine to extract the data.

Stead was very clear that a person’s vote cannot be counted twice if they vote by mail and in person.

“Some people [who are registered to vote by mail] will come to the polling place and demand that they be able to vote in person, which is certainly their right,” Stead said, if poll workers confirm that the voter’s mail-in ballot has not been received by the county. In such cases, the voter is given a provisional ballot, which is a paper ballot.

“If you are a vote-by-mail voter and you did not return your ballot by mail, then we will accept your provisional ballot,” said Stead. But if the Board of Elections receives the person’s mail-in ballot by the Monday following election, their provisional ballot will not be counted, “because we can't let you vote twice.”

Provisional ballots can also be used if voting machines were to malfunction, but that is an unlikely scenario, said Stead.

“All of our sites are pre-inspected to make sure that they can meet our electrical demands, but we do have the capability of running our machines off the battery for six hours,” he said. “If a machine goes down, or just for whatever reason isn't working, we always have more than enough spares so we can have another machine in place, usually within an hour.”

Addressing a common myth, Stead said that there is “no voting from the grave.” An individual must be alive on Election Day for their vote to count.

If a person dies before Election Day after casting a vote via mail, drop box, or early in-person voting, the vote will not be counted, because each voter’s identity is checked against the U.S. Social Security Administration’s death records. That check also alerts election officials if someone fraudulently tries to cast a vote using the identity of a deceased person.

“I'm committed to ensuring free and fair elections for everyone,” Stead said, adding that his fellow Board of Elections commissioners feel the same. “We really do accept that responsibility as something sacred and something very important to our democracy.”

This story was produced as part of the Democracy Day journalism collaborative, a nationwide effort to shine a light on the threats and opportunities facing American democracy. Read more at usdemocracyday.org.